- Home

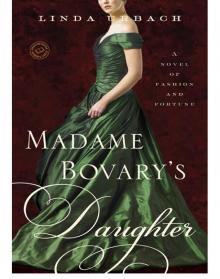

- Linda Urbach

Madame Bovary's Daughter

Madame Bovary's Daughter Read online

Madame Bovary’s Daughter is a work of fiction. All incidents and dialogue, and all characters, with the exception of some well-known historical and public figures, are products of the author’s imagination and are not to be construed as real. Where real-life historical or public figures appear, the situations, incidents, and dialogue concerning those persons are entirely fictional and are not intended to depict actual events or to change the entirely fictional nature of the work. In all other respects, any resemblance to persons living or dead is entirely coincidental.

A Bantam Books Trade Paperback Original

Copyright © 2011 by Linda Spring Urbach

Reading group guide copyright © 2011 by Random House, Inc.

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Bantam Books, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

BANTAM BOOKS and the rooster colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

RANDOM HOUSE READER’S CIRCLE & Design is a trademark of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Urbach, Linda.

Madame Bovary’s daughter : a novel / Linda Urbach.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-440-42341-6

1. Young women—France—Fiction. 2. Fashion—France—History—

Fiction. 3. Paris (France)—Fiction. I. Flaubert, Gustave, 1821–1880.

Madame Bovary. II. Title.

PS3621.R33M33 2011

813’.6—dc22 2010053286

www.randomhousereaderscircle.com

Cover images: Ryan McVay/Getty Images (woman),

Ricardo Demurez/Trevillion Images (background)

v3.1

For my daughter, Charlotte

She hoped for a son; he would be strong and dark; she would call him George; and this idea of having a male child was like an expected revenge for all her impotence in the past.… She gave birth on a Sunday at about six o’clock, as the sun was rising.

“It is a girl!” said Charles.

She turned her head away and fainted.

—GUSTAVE FLAUBERT, Madame Bovary

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Part 1: The Country Life

Chapter 1: Home Sweet Homais

Chapter 2: Her Grand-mère’s House

Chapter 3: Chores

Chapter 4: The Artist’s Model

Chapter 5: Homespun

Chapter 6: Monsieur Boulanger

Chapter 7: The Rake

Chapter 8: Another Move

Part 2: Rags

Chapter 9: The Mill

Chapter 10: First Day of Work

Chapter 11: A Visitor to the Factory

Chapter 12: A Den of Thieves

Chapter 13: The Boots

Part 3: Into the Fire

Chapter 14: The Convent

Chapter 15: A Palace in Paris

Chapter 16: The Master Returns

Chapter 17: The Bath

Chapter 18: Family & Friends

Chapter 19: Lesson in Love

Chapter 20: Monsieur Worth Has Some News

Chapter 21: Madame Has a Surprise

Chapter 22: La Grande Fête

Chapter 23: Yet Another Artiste

Chapter 24: Watching Paint Dry

Chapter 25: A Visit to the Louvre

Chapter 26: Dreams and Reality

Chapter 27: The Birthday Ball

Part 4: Work and Love

Chapter 28: Reunion

Chapter 29: A Shopping They Will Go

Chapter 30: The Young Man from Germany

Chapter 31: A New Opportunity

Chapter 32: A New Chapter

Chapter 33: Sunday Afternoon

Chapter 34: Busy Days, Beautiful Nights

Chapter 35: Old Friends, New Money

Chapter 36: A New Gown

Chapter 37: Love and Work

Chapter 38: The Other Shoe

Epilogue

Author’s Note

Acknowledgments

A Reader’s Guide

About the Author

CHAPTER 1

Home Sweet Homais

YONVILLE, 1852

WAS ANY DAUGHTER EVER CURSED WITH A MOTHER SUCH AS hers? A self-centered, social-climbing, materialistic, coldhearted, calculating adulteress. Oh, yes, and she disliked children, too.

Everyone in the village of Yonville and the city of Rouen and all the towns in between knew the story of her mother’s disastrous affairs; her wastrel ways; her total disregard for her husband, his reputation, and his finances. And her complete disinterest in Berthe, her only child. It was her mother’s friend, Madame Homais, who put it into words for Berthe on the day of her father’s funeral. Yes, even at her father’s funeral they were still gossiping about her mother, who had poisoned herself almost a year before.

“Your poor, dear mother. She always wanted what she couldn’t have,” Madame Homais said as she pulled a comb through Berthe’s long snarled hair. Berthe hadn’t brushed her hair in weeks or possibly even months, ever since her father had fallen ill. “And what she had, she didn’t want. As for your papa, all he wanted was just a little of her love. Mon Dieu, what a rat’s nest.” She untangled the comb from the girl’s hair, then gave Berthe a gentle push. “Now go and put on your best dress.” Did she know that Berthe only had two dresses to her name? Neither could be described as “best.” All the pretty dresses that she had once owned had been sold months before. There was nothing left but the house, and that was going to be auctioned off in an effort to make a small dent in her father’s enormous debt.

It was a beautiful spring day. Much too beautiful a day on which to be buried. The bright sun shone down on the small market town. Surrounded by pastureland on one side and the Rieule river on the other, Yonville boasted one main street. Lining the street and the large square were a chemist’s shop, a blacksmith’s shop, a simple vegetable market, the town hall—designed by a Parisian architect who favored the Greek Revival style—and the almost famous Lion d’Or Inn. On cramped side streets were the residential houses. It was a snug, self-contained little village only twenty-four miles from Rouen.

The entire village attended Charles Bovary’s funeral. He had been, after all, the town physician. And beyond that, the villagers had great sympathy for him. He had died quite simply of a broken heart and everyone knew it. Berthe kept her head down so she wouldn’t see all the people staring at her with their sad eyes. They just want to see me cry, she thought. But she wouldn’t cry. She couldn’t cry. On what was supposed to be the saddest day of her life she felt only a paralyzing, numbing fear. She looked down at her hands. Her nails were bitten to the quick and she had never been a nail-biter.

She knew that being orphaned was not an unusual situation. How many times had her father told her about the many orphans who littered the land as a result of sickness, war, or the normal hardships of a poverty-stricken life? But Berthe wasn’t an ordinary twelve-year-old orphan, as people of the village kept reminding her. She was the progeny of the most scandalous woman who ever lived.

“How will the poor thing make her way in the world?” she heard someone whisper behind her.

“Perhaps, like mother like daughter,” said her companion.

“Don’t forget her father. He was a decent man, after all.”

“Much good that did.”

“She has the beginnings of her mother’s beauty. That in itself does not bode well.”

“She is a strange child. But is it any wonder? With a mother like that?”

Berthe shot a lo

ok at the woman. She wanted to scream I’m not a strange child, and tear the hypocritical mourning veil off the woman’s head. Where were the reassuring words? Weren’t they supposed to tell her everything was going to be fine? She looked around. All she saw was a row of black-clad women—a line of crows shaking their heads in disapproval. Her terror grew. She felt as if she were taking the last steps to her own funeral.

Suddenly she was visited by the image of both her parents’ deaths: her mother from self-administered poison and her father from a self-acknowledged broken heart. She saw her mother in those last moments, her pale waxen features, her eyes covered with a kind of second skin, her mouth, that black poisoned hole sucking in air, and her curled hands picking aimlessly at the sheets. Her father sitting under the oak tree, his head bent, his eyes half open, his jaw unhinged. Dead to the world—and to his only daughter, who had come out to the garden to wake him for a dinner he would never eat.

So strong, so vivid was this image of her dead parents that she felt herself gag. She thought she was going to be sick in front of everybody. Sweat broke out on her forehead and she wiped it away with the back of her hand.

“Stand strong, dear child, it will all be over soon,” said Madame Homais, taking her wet hand and squeezing it tight.

After Emma Bovary died her husband spent a fortune on designing and building an elaborate granite mausoleum complete with cherubs and crucifixes. He had even begged money off his good friend Monsieur Homais with the promise that he would repay the loan in a timely fashion. How he was going to do that was a mystery, considering the fact that he had already pawned his instruments and medical books. Monsieur Homais was ignorant of this and assumed that Charles would be back on his feet as soon as his mourning period was over. It was never over.

As they drew nearer to the mausoleum, Monsieur Homais looked up at his friend’s final resting place. He shook his head sadly. “This could have been Madame Homais’s much-wished-for third bedroom,” he muttered to Berthe. It was a good thing his wife had no knowledge of her husband’s loan.

The crows continued to rustle their black capes and whisper in all-too-audible tones as Berthe passed by, following her father’s coffin.

“She spent all his money on herself,” one said.

“And someone else,” said another. “Don’t forget the Someone Else.”

“No one is about to forget that little piece of scandal.”

“You know there were two.”

“No!”

“Oh, yes. Do you remember young Monsieur Léon?”

“But he left town.”

“He may have left town, but he didn’t leave her.”

“Really!”

Several women gasped and covered their mouths with their black-gloved hands. Their eyes gleamed in anticipation of hearing more.

Because of the size of the mausoleum, Charles Bovary’s coffin could not be placed directly next to his wife’s but had to be wedged in at a perpendicular angle at the end of her triple-enclosed casket. The four men who had carried the coffin from the village struggled to fit it in. Thus, Madame Bovary’s husband was laid to rest literally at her feet. And given the state of his estate, or the lack thereof, an expensive coffin for him was out of the question. He had been put in the plainest of pine boxes. It made a curious sight: the rough-hewn pine coffin lying at the foot of the lustrous rosewood casket like a humble servant at the feet of his beloved queen. The four pallbearers stepped out, rubbing their sore hands together. Then the Homaises and Berthe squeezed in what little space was left while the rest of the villagers had to make do with paying their respects from outside.

So, Berthe thought, her mother would be housed for eternity in the luxury she had always yearned for. How many years and how much money had she spent stuffing their humble home with the trappings of a much grander establishment? Silk damask armchairs, Chinese screens, crystal candelabras, brass andirons, heavy brocade curtains, a hand-carved prayer kneeler, a graceful four-poster bed. And when her husband occasionally protested, she explained: “We will need these things when we move to the new house.”

She held out this vision of a grand dwelling as though it were a reality. Her dream house was based on her one visit as a young bride to the château at Vaubyessard. She described her visit often and in great detail to Berthe. It was her idea of a bedtime story.

“I walked up three flights of marble steps and into the great hall. As I looked up I saw a chandelier hanging from a glass dome. It was made of a million crystals that caught the light and glittered so brightly it hurt my eyes. There was a pink marbled staircase that circled around and up to a gallery. The walls were covered in silk. The air smelled of roses and lilacs.”

But in Emma Bovary’s mind, it was the effect this splendid château had on its inhabitants that was so magical. The château seemed to transform every person in it.

“They were ordinary men and women but they looked like they were another species altogether. Their hair was more lustrous, their skin had a polish and glow, their smiles were more brilliant. Their happiness was unlike anything I had ever seen before or since. It was being in that house that made them so happy and so beautiful.”

Thus, Berthe had grown up with two homes, the slightly shabby lodging they lived in and the luxurious château of her mother’s memory. The bills mounted and her mother began to sell off small decorative items before her husband discovered her secret debt. As little by little the house in Yonville grew shabbier, Berthe still had that other more enduring abode of her mother’s fantasy. Where there would be no gossip, no suffering the opinion of others, no creditors, no shortage of love, no shortage of beautiful things to buy. And where her mother continued to live in this happy, happy home where no one and nothing could ever hurt her.

Berthe recognized a fairy tale for what it was. She knew her mother had lived much of the time in another world and that her fantasies had created an impenetrable wall around her. On the one hand, Berthe deeply resented the stories that separated her mother from their real life. On the other hand, the fairy tales held a magic that was difficult for a little girl to resist.

Her mother’s favorite stories came from her beloved books. She spent hours and hours reading, happily lost in the pages of her novels. Every once in a while, she would read aloud. Emma Bovary seemed to require an audience for these recitations. Their maid, Félicité, was of course too busy, and that left Berthe as the most likely candidate.

All of the books had to do with true love, tragic love, unrequited love, doomed lovers, beautiful maidens in distress, gallant heroes coming to their rescue, fainting ladies in perfumed gardens, magnificent mansions, glorious châteaux, bloody battles, hearts won and lost and won again, dastardly villains, and untimely deaths, always in lush surroundings with exquisitely dressed women showing much ivory skin and tall, handsome men on their equally tall and handsome horses. Much later, Emma Bovary acquired a taste for modern novels by the English author Jane Austen. She also adored the stories of Mary, Queen of Scots, and Joan of Arc. Sir Walter Scott was another of her preferred authors. When she read “The Lady of the Lake” aloud to Berthe, the rhyming sometimes put her young daughter to sleep.

“Berthe, wake up. I’m coming to the best part.”

“But, Maman, it is so long it makes me tired.”

“How anyone can sleep through such beauty is beyond me.” Her voice took on a faraway tone as she recited:

“A chieftain’s daughter seemed the maid;

Her satin snood, her silken plaid,

Her golden brooch, such birth betrayed.

And seldom was a snood amid

Such wild luxuriant ringlets hid,

Whose glossy black to shame might bring

The plumage of the raven’s wing …

“Berthe, I’m not going to waste my breath if you’re not going to pay attention. Go away and play with your dolls,” she said angrily.

Berthe’s sleepy head filled with visions of golden brooches and satin s

noods, and she too became entranced with the stories, the romance and the richness, the drama and damsels. But most of all she loved the words. Words read aloud. Words on paper like so many stitches of embroidery. She listened to the words, long and luxurious, perfect as silk thread. She marveled at how a collection of words could create a fantastic story out of nothing.

When her mother left her to play alone (more frequently than not) Berthe created her own fairy tales using herself as the fabled princess. One day she pulled down a lace curtain that was drying on the clothesline behind the cottage and wrapped herself in it. She began humming softly as she paraded up and down the small yard. The sun shone down on her lace-covered head as if bestowing a special blessing. I am the queen of the world. The beautiful queen of the world.

“What in heaven’s name are you doing, you wicked girl?” Her mother snatched the curtain from her. “Now Félicité has to wash this all over again!”

It was cold and dark in the mausoleum. Berthe could barely make out the faces of Madame and Monsieur Homais. She could feel the chill of the cement floor through her thin boots. She stared at the two dramatically different caskets. Suddenly she could bear it no longer. She pulled the green velvet covering from her mother’s casket and placed it on her father’s. Monsieur Homais patted her shoulder.

“Poor fellow. He is the one who should have had the finer coffin. Perhaps we should switch the coffins as well,” he said, half in jest.

“Hush, you idiot!” Madame Homais said, hitting him on the arm. Berthe couldn’t help but notice the amusement on her face. She was such a strong, warm, comforting woman. Berthe wondered what it would be like to be her daughter. In her mind, she wailed at her mother. How could you do this to Papa? Didn’t you know he would die without you? Didn’t you care? You have killed everything.

Madame Bovary's Daughter

Madame Bovary's Daughter